Parents and Children in C++

When reversing C++ binaries, identifying Inheritance is important. Derived Classes contain Base Class data at predictable offsets, creating recognizable memory patterns. By analyzing constructor calls, vtable pointers, and object layouts in a disassembler, we can reconstruct class hierarchies. This understanding is essential for interpreting Polymorphism and Virtual Functions in assembly.

One parent is enough

Lets begin with single inheritance, one parent. We’ll be taking the following code as an example:

class Base

{

public:

int int_Base;

Base(int x)

{

this->int_Base = x;

}

int getVal()

{

return int_Base;

}

};

class Derived : public Base

{

public:

int int_Derived;

Derived(int x, int y):Base(y)

{

this->int_Derived = x;

}

int getVal()

{

return int_Derived;

}

};

int main()

{

Derived obj_D(1,2);

int var = obj_D.getVal();

return 0;

}

our class Derived inherits from class Base. Both have a single integer variable and parameterized constructors, and class Base has a member function of getVal().

Lets compile it using G++

# compile a C++ program

g++ singleInheritence.cpp -o singleInheritence

Static Analysis using IDA

Lets dive deep into it by taking a look at the disassembly generated by IDA:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 20h

mov rax, fs:28h

mov [rbp+var_8], rax

We have our function prologue at lines 1 and 2, then we allocate a space of 0x20 on the stack (32 bytes) and then save our stack canary or stack cookies.

xor eax, eax

lea rax, [rbp+var_10]

mov edx, 2 ; int

mov esi, 1 ; int

mov rdi, rax ; this

call Derived::Derived(int,int

The compiler uses [rbp+var_10] to store the current object, and loads its address into rax, making it the this pointer for later instructions. We see that our parameters are set in rdi, rsi and rdx as address of our object on stack, 1 and 2 respectively. Lets make the constructor call..

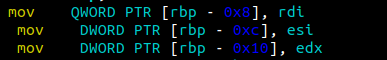

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 10h

mov [rbp+var_8], rdi

mov [rbp+var_C], esi

mov [rbp+var_10], edx

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov edx, [rbp+var_10]

We can see the function prologue, followed by an allocation of 0x10 bytes on the stack, and then how our arguments are getting saved on the stack relative to our new rbp. Our this pointer gets saved at [rbp + var_8] as seen in line 4 which later gets loaded in rax, and our arguments in registers rsi and edx also get saved on the stack at locations [rbp+var_C] and [rbp+var_10] respectively.

mov esi, edx ; int

mov rdi, rax ; this

call Base::Base(int)

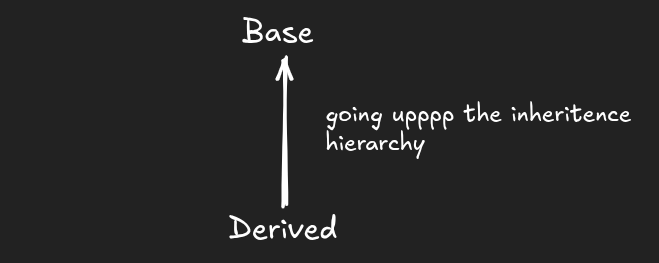

Later we see that that we are again setting parameters for a call to Class Base’s constructor which expects int as an argument… Before the Derived class constructor runs, the Base class constructor is automatically called to make sure the Base portion is properly initialized before Derived. Constructor calls keep moving up the inheritance hierarchy until the topmost base class has been constructed.

And here comes our Base constructor:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov [rbp+var_8], rdi

mov [rbp+var_C], esi

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov edx, [rbp+var_C]

mov [rax], edx

nop

pop rbp

retn

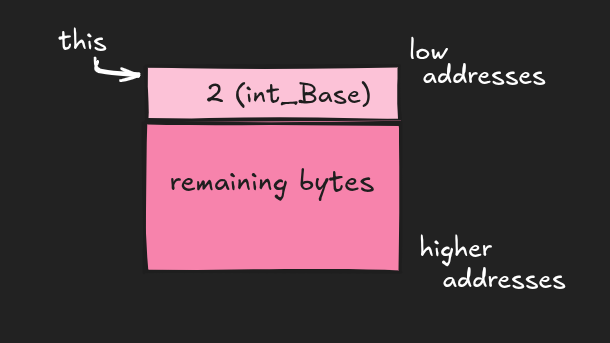

it stores the contents inside esi, which is actually the value int_Base is initialized to on this constructor call, to the location where this pointer points to on the stack, and then it returns. Our obj_D currently looks like this:

Recall that our

Recall that our Base class also had a member function getVal(), but it is not getting stored anywhere inside our object. This is because member functions live in the program’s code section, not in each object, so only data members are stored inside the object. Anyway lets return back to our Derived constructor now.

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov edx, [rbp+var_C]

Recall, that rbp+var_8 stored our this pointer, and var_C stored our second argument which comes in esi. The second argument is the value with which the data member of our Derived Class, that is int_Derived needs to be initialized with since that is the order we followed in our code snippet.

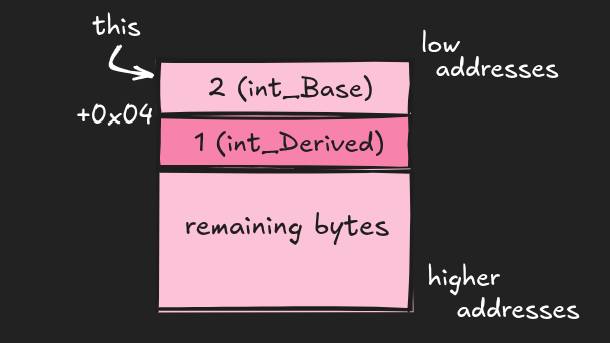

mov [rax+4], edx

We now store the value of int_Derived inside our object, since rax is referencing it, but at an offset of +0x04. Why so? Well… that’s because our Base class also has an integer data member int_Base, which is stored in our object before any data member of Derived is. Integer takes 4 bytes, and since there are no padding issues yet, so we simply skip those 4 already colonized bytes, and land at address rax+4, and this is where we store the newly set value of int_Derived, that is 1.

nop

leave

retn

now we encounter our function epilogue for our Derived Class’ constructor, and lets return back to our main function.

lea rax, [rbp+var_10]

mov rdi, rax ; this

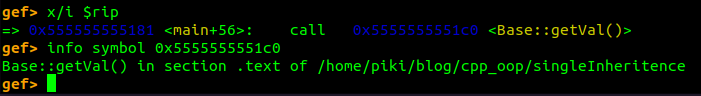

call Base::getVal(void)

Now, when control returns to main, we want to call the getVal() member function that belongs to the Base class. Since our Derived class inherits from Base, it automatically gains access to all the public and protected members of Base (except constructors and destructors). We set rdi as this pointer which points to our Derived class object, and call our getVal() function… There’s nothing much inside getVal()’s body, but lets just see it:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov [rbp+var_8], rdi

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov eax, [rax]

pop rbp

retn

This function simply dereferences the this pointer, and reads the 4 bytes (an int) from the memory address that rdi points at, and then places that value in eax.

mov [rbp+var_14], eax

on returning, we simply take the value in eax, and store it in our local variable var which is at rbp+var_14. And then we simply end our main too… so that’s pretty much it. This was static analysis, lets take a look at it with dynamic analysis using GDB so that things get clearer.

Dynamic Analysis using GDB

Lets start!

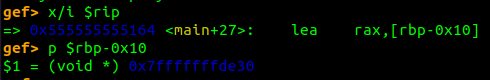

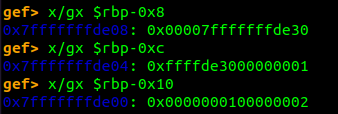

At this instruction, we’re retrieving our object’s address, which is our this pointer. It’s address is 0x7fffffffde30.

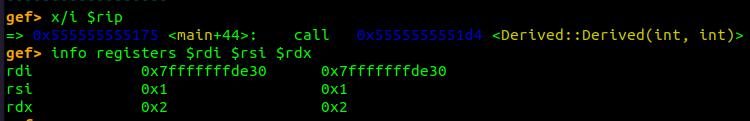

We then set our registers with the correct parameters, and call our Derived Constructor. Note that rdi holds our the address of our object.

in our Derived constructor, we save our arguments on the stack.

next we set up our registers for a call to

next we set up our registers for a call to Base(int).

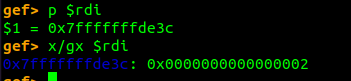

In Base constructor, we simply set our value of int_Base inside the object. lets analyze the memory contents after we are done with setting our value.

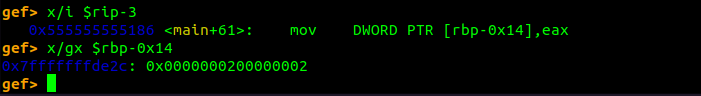

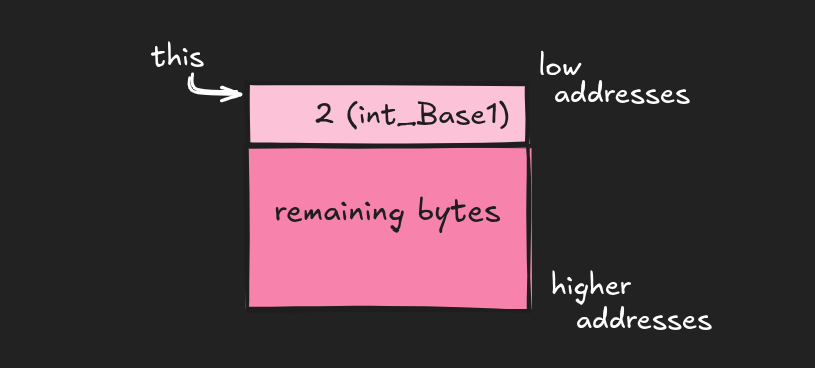

We see, 0x2 is right at the start of our object. Once we return from Base constructor, now we can run our Derived constructor. Had there been any other class from which Derived inherited, we would’ve visited its constructor too as we’ll soon see… but since there’s not any, we’ll let Derived continue with its execution, where it sets the value of its data member int_Derived at offset of +0x04 from the address of our object obj_D. Lets see the memory layout after it’s done:

Eureka! Lets return to our main now…

We give a call to Base::getVal(), store the return value in eax, and save it in a local variable at rbp-0x14.

When the compiler decides early

In the above example, we had a simple case where we simply created a Derived class object on the stack… But what if we do something like…

Base *b = new Derived(4,5);

int var = b->getVal();

Where the object is getting created on the heap. Which getVal() is this going to trigger? Lets take a look in IDA:

mov rax, [rbp+var_18]

mov rdi, rax ; this

call _ZN4Base6getValEv ; Base::getVal(void)

rbp+var_18 holds our this pointer, which will be pointing to a location on the heap, since this time we’ve used new operator for object creation. We see, that the function getting called is Base:getVal(void), and not Derived:getVal(void). Shouldn’t it call Derived’s getval() since the object type is of Derived class? Well, the answer is no. Lets get familiar with a fancy term, static binding. This is static binding. Static binding means the compiler decides at compile time which function to call. It doesn’t care what the object actually is at runtime, it only looks at the declared type of the pointer or reference. the compiler sees b pointer as Base type, and decides that it will always call Base::getVal(). If the compiler only sees the type of b, does it mean, that it doesn’t recognize anything of Derived? Lets try this out.

I’ve added a function foo() inside my Derived class:

void foo() {}

lets try calling it in main: ```cpp ln=33 int main() { Base *b = new Derived(4,5); b->foo();

return 0; } ``` try compiling it and we get some pretty decent errors:

g++ singleInheritence.cpp -o singleInheritence

singleInheritence.cpp: In function ‘int main()’:

singleInheritence.cpp:36:4: error: ‘class Base’ has no member named ‘foo’

36 | b->foo();

| ^~~

Well then why does the compiler allow us to create an object this way, as we just created, if our b is going to be blind to Derived’s members? Because of inheritance and type compatibility.Derived is-a Base (since class Derived : public Base). That means every Derived object contains a Base subobject inside it. When we do something like…

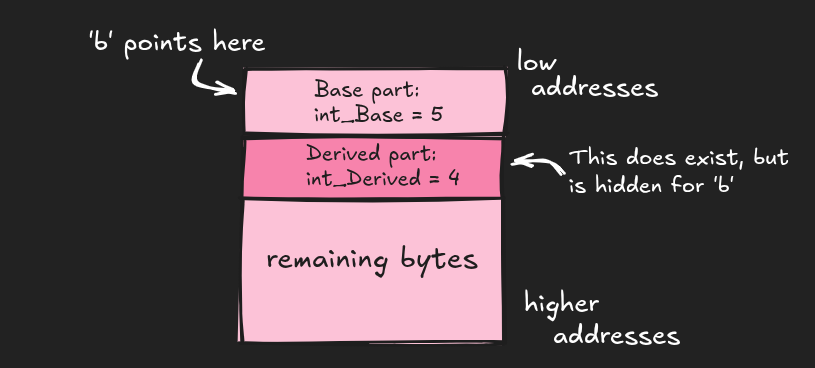

Base* b = new Derived(4,5);

new Derived(4,5) creates a Derived type object in memory. This object is going to have two parts, the Base part and the Derived part.b points only to the Base part of the Derived object and only cares about Base members.

Seeing the child as the parent..

This introduces us to a new concept, called Upcasting…

Derived* d = new Derived(4,5);

Base* b = d;

We’re taking a Derived object and casting it up the inheritance hierarchy to be treated as a Base object.

If we look at it from a memory perspective:

If we look at it from a memory perspective:

To make invocations to Derived’s member functions possible even after doing so, we use virtual functions which are out of the scope of this discussion.

When one parent just isn’t enough

Now we’ve seen inheritance in case of single inheritance only, but what if, we have a case of multiple inheritance, where a single class inherits from multiple classes? Lets dive into this. Lets first rename our Base class as Base1 and the new base class our Derived will inherit from will be Base2 class.

class Base1

{

public:

int int_Base1;

Base1(int y): int_Base1(y) { }

};

class Base2

{

public:

int int_Base2;

Base2(int z): int_Base2(z) { }

};

class Derived : public Base1, public Base2

{

public:

int int_Derived;

Derived(int x, int y, int z):Base1(y), Base2(z), int_Derived(x) { }

};

int main()

{

Derived obj_D(1,2,3);

return 0;

}

I’ll jump directly to the part where we’re calling our Derived’s constructor from main:

lea rax, [rbp+var_24]

mov ecx, 3 ; int

mov edx, 2 ; int

mov esi, 1 ; int

mov rdi, rax ; this

call Derived::Derived(int,int,int)

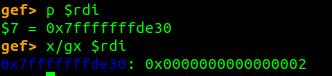

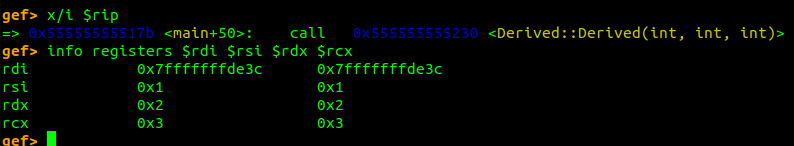

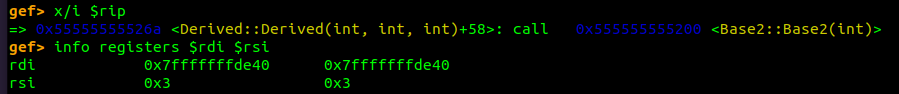

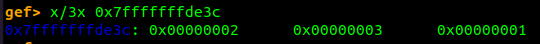

side by side, we’ll be seeing GDB too, so the parameters we have are:

this shows that the address of our object is 0x7fffffffde3c. In our Derived constructor, we first make a call to Base1’s constructor with appropriate parameters:

mov esi, edx ; int

mov rdi, rax ; this

call Base1::Base1(int)

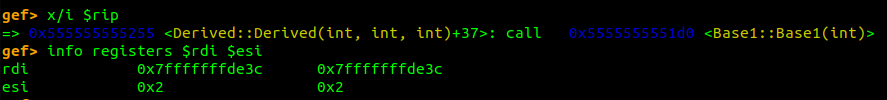

in GDB:

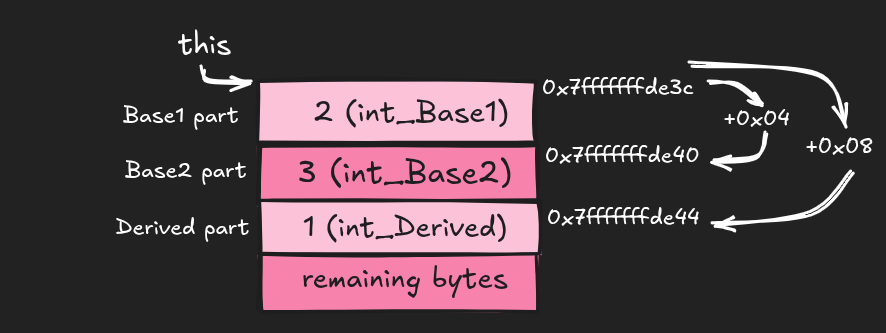

In Base1’s constructor, we simply store the value 3 at offset 0 inside our object, giving us the intermediate object state as..

till now, our object looks something like this…

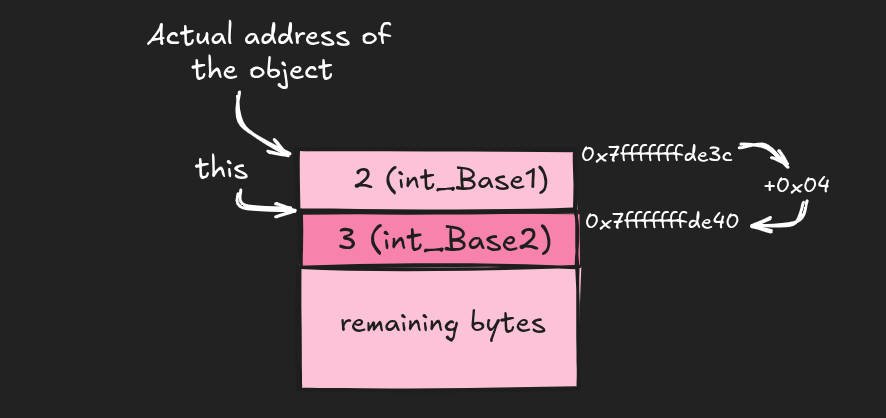

Once we return from Base1 constructor, we call Base2’s constructor, but with a different this pointer value.

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

lea rdx, [rax+4]

mov eax, [rbp+var_14]

mov esi, eax ; int

mov rdi, rdx ; this

call Base2::Base2(int)

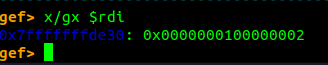

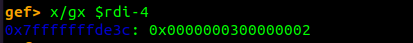

rax gets initialized with the address of the object, that is the this pointer, we add 0x04 to it and load its address in rdx, and this address gets passed as the address of the object.

the actual address of our object is 0x7fffffffde3c, and after addition of 0x04 it becomes 0x7fffffffde40.

seeing this in GDB…

Once we return from Base2 constructor, we then store the value of int_Derived inside our object:

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov edx, [rbp+var_C]

mov [rax+8], edx

All three data members

All three data members int_Base1, int_Base2 and int_Derived have been stored inside the object obj_D now…

Then we return to main, check the stack canary, encounter our function epilogue, and that is pretty much it.

Happy Reversing!