The Virtual Functions

Since we’re done with the basics, lets start reversing our magnificent virtual functions…

So, what’s the deal with virtual functions?

Virtual functions are C++’s way of enabling runtime polymorphism, which is the ability for the program to decide at runtime which version of a function should be executed depending on the actual object type, not just the pointer type.

Let’s first take a look at a simple example, of a single class having virtual functions.

class Ex1

{

int var1;

public:

virtual void foo();

virtual void bar();

virtual ~Ex1();

};

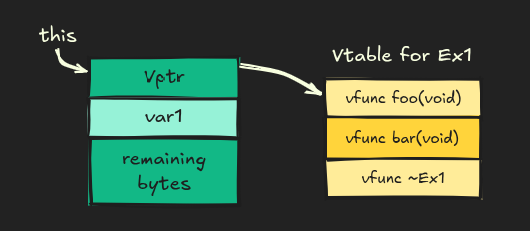

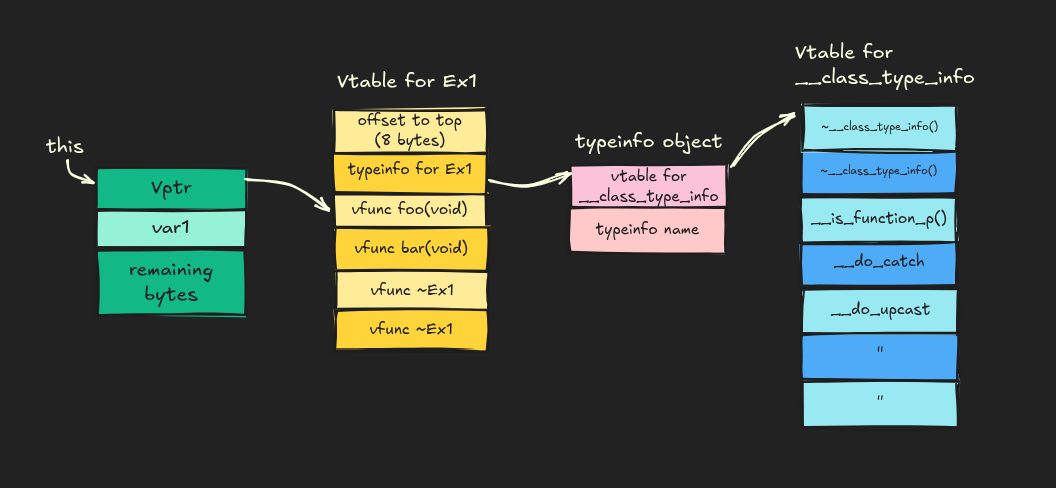

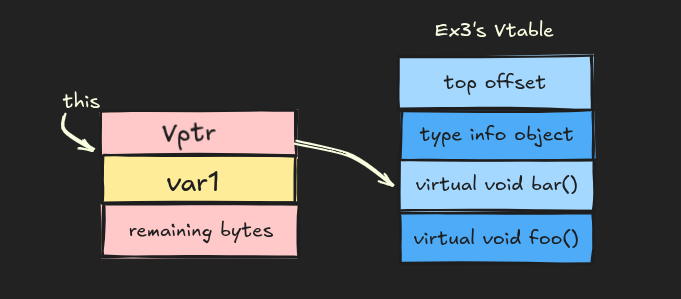

We have a simple class Ex1, having three virtual functions, foo(void), bar(void) and a virtual destructor. When we mark a function as virtual, the compiler arranges things differently inside the object. Each object of Ex1 now contains a hidden pointer called the vptr (Virtual Table Pointer) right at the start of the object. The size of vptr depends on the architecture, and since we’re on a 64-bit architecture, vptr is 8 bytes (it will be 4 bytes in a 32 bit architecture). The vptr points to a table in memory known as the vtable. The vtable is simply an array of function addresses, one for each virtual function. So in our case, we assume that the vtable for Ex1 will have three entries, one for foo() , second one for bar() and the third one for the destructor ~Ex1. If we invoke foo(), the program won’t directly call it like how we’ve seen till now. Instead, it looks up the foo entry in the vtable and calls the function address stored there.

However later we’ll see, that there’s a lot more to a vtable than entries of virtual functions alone. Here’s our main function…

int main(int argc, char** argv, char** envp)

{

Ex1* obj = new Ex1;

return 0;

}

Lets take a look at the assembly IDA generated for us:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

push rbx

sub rsp, 38h

mov [rbp+var_24], edi

mov [rbp+var_30], rsi

mov [rbp+var_38], rdx

First we have our function prologue from line 1 to 2, then we save our callee-saved register rbx on the stack on line 3, then we allocate a space of 0x38 on our stack on line 4, and then save the arguments to main() which were argc, argv, and envp on the stack, relative to rbp between lines 5 and 7.

mov edi, 10h ; unsigned __int64

call operator new(ulong)

We want to allocate 16 bytes for our object… We have 4 bytes for our var1 data member, and our vptr is taking up 8 bytes. That makes a total of 12 bytes (4+8), but because of 16 byte alignment, we round it up to 16 bytes (0x10). After returning from operator new, our rax now holds the address of our newly allocated 16 bytes, which is our object.

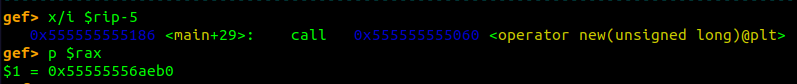

Lets see the address of our object in GDB:

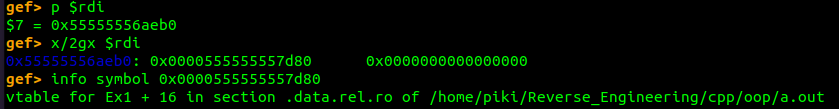

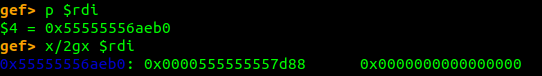

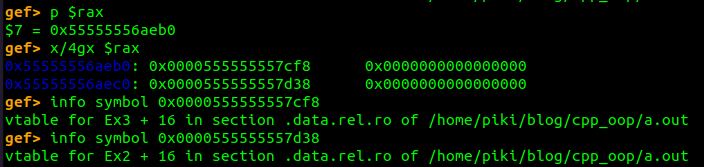

Address of our object is 0x55555556aeb0. Continuing to the disassembly…

mov rbx, rax

mov qword ptr [rbx], 0

mov dword ptr [rbx+8], 0

In these lines, we simply first zero out the memory…

mov rdi, rbx ; this

call Ex1::Ex1(void)

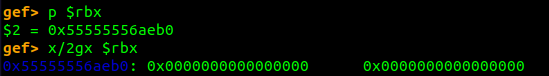

and then we call our constructor Ex1. Lets check this:

and now…

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov [rbp+var_8], rdi

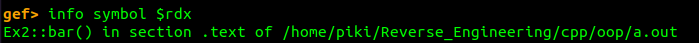

lea rdx, off_3D80

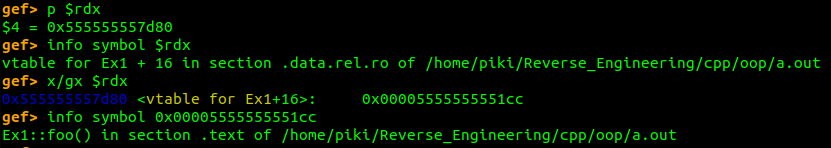

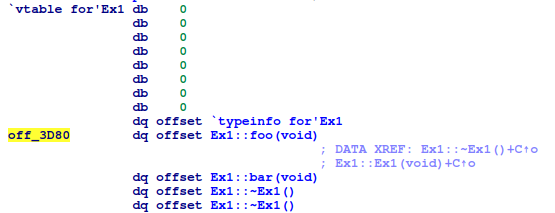

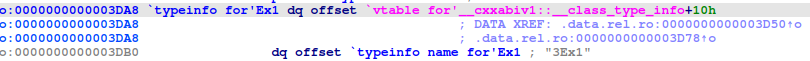

We are inside our Ex1 constructor, and after our function prologue and saving our this pointer on the stack, we notice that the address of off_3D80 is getting loaded in rdx… If we double click on it in IDA, it takes us to the first virtual function entry in our vtable of Ex1.

off_3D80 dq offset Ex1::foo(void)

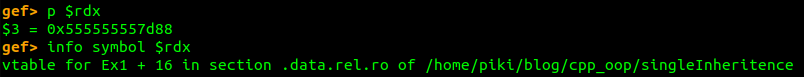

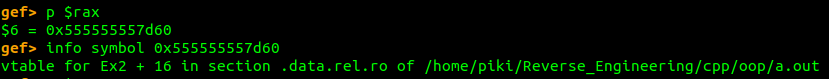

seeing it in GDB…

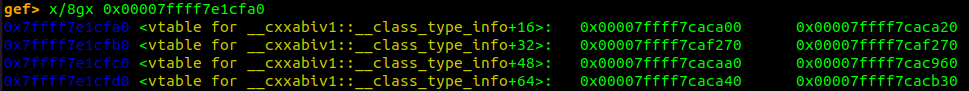

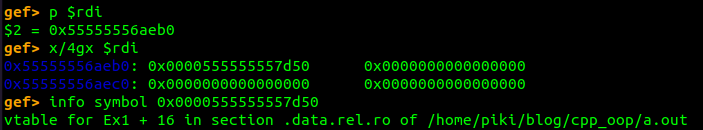

We see that rdx holds the address of the vtable. When we examine the memory at the vtable, we get our first virtual function address. But we can see that the address that is getting loaded in rdx is vtable for Ex1 + 16. Why the addition of 16 bytes?

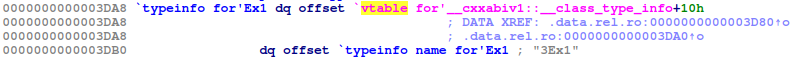

This is our complete vtable, it doesn’t hold the addresses of our virtual functions alone, but it has other stuff. In the start, we see 8 null bytes, this is our offset to top. It’s a small integer stored in the vtable that tells at runtime how far the current subobject is from the start of the complete object in memory. But here since it’s 0, so this indicates that this vtable belongs to the main class and our object doesn’t consist of a subobject as we have a single class (no inheritence), so no adjustments are needed. This entry is placed two slots before the vtable pointer, at index -2. It exists in all vtables, even in classes that have virtual bases but no virtual functions.

Below the 8 byte offset to top, we have our typeinfo pointer.

What in the world is a ‘typeinfo’…

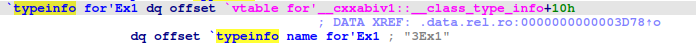

What is typeinfo for Ex1? typeinfo for'Ex1 is a runtime type information (RTTI) object that exists in our binary’s data section. Every virtual table has a special entry that points to an object derived from std::type_info. This entry sits at one slot before the address stored in the object’s virtual pointer which is the address of the first virtual function, that is, at index -1. This type_info pointer is present in all vtables. In the case of type_info itself, we have to add its own virtual table pointer because the class has a virtual destructor.

One of the possible derived type from type_info which is of our interest in the current scenario is __class_type_info. __class_type_info is the GCC C++ ABI implementation for simple classes that either have no inheritance at all or serve as base classes for others. Lets take a look at its declaration in the C++ Standard library:

class __class_type_info : public std::type_info

We see, that it publicly inherits from type_info. type_info has a number of functions, both virtual and non-virtual and a protected member, const char *__name. Our __class_type_info’s constructor looks something like this:

explicit __class_type_info (const char *__n) : type_info(__n) { }

We notice that the constructor of type_info expects a char pointer (__n) as an argument.

This pointer is then stored inside the class by assigning it to the member variable __name.

protected:

const char *__name;

explicit type_info(const char *__n): __name(__n) { }

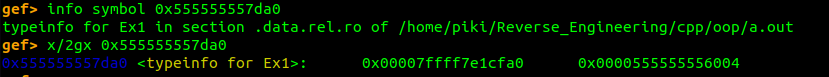

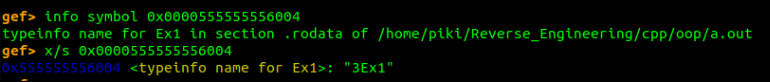

Anyway, back to our typeinfo for Ex1. Since __class_type_info itself has virtual functions, and so does type_info, so its object layout must include a vptr. So, at 0x0, the object stores a pointer to the vtable for __class_type_info. Type Name Pointer at +0x08 points to the mangled name string of the class which in this case is 3Ex1. This type name is actually the *__name we just discussed in type_info class. Lets double click typeinfo which will bring us to…

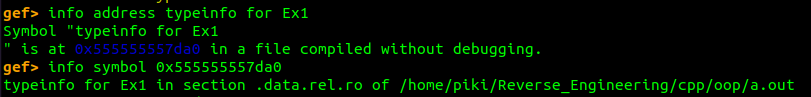

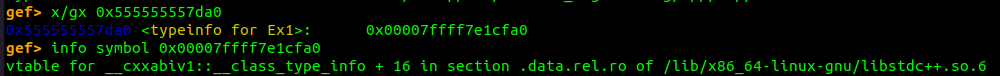

Lets locate our typeinfo object:

the address where our typeinfo object for class Ex1 is located in memory is 0x555555557da0. If we examine the contents at our typeinfo object’s address, we see that it holds the address of __class_type_info’s vtable.

Lets see what the vtable further holds…

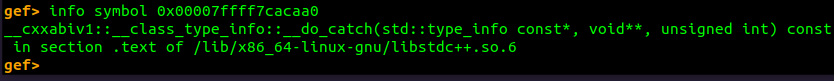

lets pick a random address, say 0x00007ffff7cacaa0.

It is the address of __do_catch(args) which is a member function of __class_type_info

virtual bool __do_catch(const type_info* __thr_type, void** __thr_obj, unsigned __outer) const;

We just discussed the type name pointer which is at offset of +0x8 from the typeinfo object, lets now actually see it:

The first address we see we just saw is the address of __class_type_info’s vtable, so the second one is going to be our type info name.

Lets return back now! Recall that we defined only 3 virtual functions, but our vtable has entries for 4 virtual functions.

What’s with the extra destructor?

Lets dig in…. Below are the two virtual destructors which live in our vtable.

.data.rel.ro:0000000000003D90 dq offset Ex1::~Ex1()

.data.rel.ro:0000000000003D98 dq offset Ex1::~Ex1()

The first destructor we see at 0x3D90 actually restores our vtable. Take a look at its disassembly:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov [rbp+var_8], rdi

lea rdx, off_3D80

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov [rax], rdx

nop

pop rbp

retn

We restore our vtable’s address at offset 0x0 of our object which causes vtable pointer (vptr) to point back to Ex1’s vtable. This happens before calling destructors of member variables to make sure that if any member destructors call virtual functions, they call Ex1’s version, not a base class version. This much detail is enough for now, and we can keep this as a topic for another discussion. Lets see the second destructor:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 10h

mov [rbp+var_8], rdi

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov rdi, rax ; this

call Ex1::~Ex1()

At line 7, it calls our first destructor, which we just discussed. This restores the vptr back to offset 0x0 in our object, and then…

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov esi, 10h ; unsigned __int64

mov rdi, rax ; void *

call operator delete(void *,ulong)

leave

retn

We delete our object from memory. Recall, that we allocated 16 bytes (0x10) for this object, so we pass that as our size. This shows, why two destructor were needed, and added to the vtable. Till now we’ve seen how our vtable actually looks like.

Lets return back to Ex1’s constructor, after having loaded the effective address of Ex1’s vtable in rdx.

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov [rax], rdx

nop

pop rbp

retn

We simply store the address of our Ex1 vtable at the start of our object.

Now we return back to main… and this is pretty much it!

Single Parent with Virtual functions…

Since we are nicely done with how our virtual functions look like in memory, we’ll dive into how they actually come handy. For this, we’ll deal with a case of single inheritance involving virtual functions. We’ll be dealing with the following example:

class Ex1

{

private:

int var1;

public:

void foo()

virtual void bar()

};

class Ex2: public Ex1

{

private:

int var2;

public:

virtual void foo()

void bar()

};

We have two classes, both have a single virtual function. Ex2 inherits from Ex1. In the main function, we create an object using new:

Ex1 *obj = new Ex2();

Lets directly dig into the disassembly where our object gets created:

mov edi, 10h ; unsigned __int64

call __Znwm

We allocate a 16 byte object on the stack. The address our function is allocated at is 0x55555556aeb0.

and then..

mov rdi, rbx ; this

call Ex2::Ex2(void)

We zero out our memory area, and call our Ex2 constructor.

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 10h

mov [rbp+var_8], rdi

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov rdi, rax ; this

call Ex1::Ex1(void)

Once we’re inside the Ex2 constructor, we give a call to our parent constructor, Ex1.

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 10h

mov [rbp+var_8], rdi

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov rdi, rax ; this

call Ex1::Ex1(void)

In our Ex1 constructor, we save the address of our Ex1 vtable at offset 0 of our newly created object.

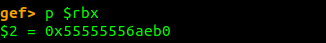

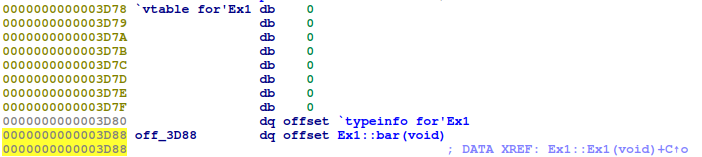

mov [rbp+var_8], rdi ;rdi holds this pointer

lea rdx, off_3D88 ;vtable for Ex1

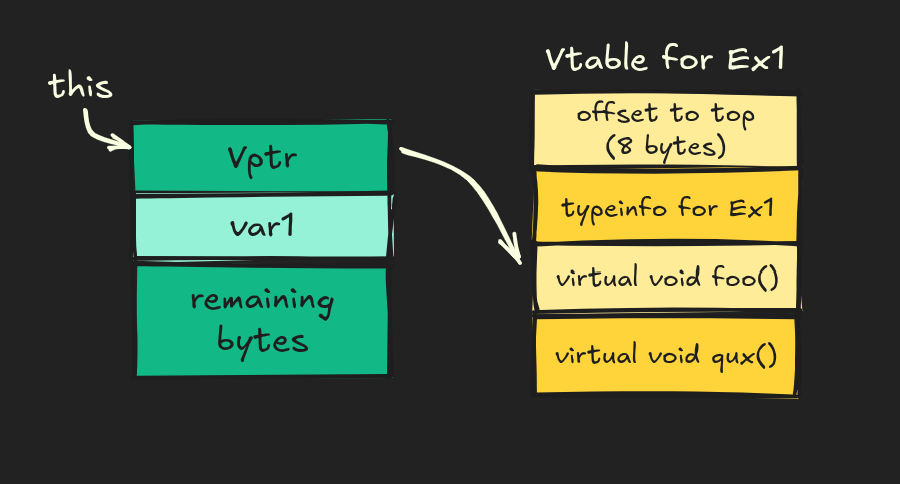

Lets dig into our vtable for Ex1.

First comes the offset to top that is 0x0, and then comes the typeinfo pointer as we’ve already seen. Our vtable has only a single entry in the vtable, for the function bar(). This is because foo() is not virtual, and vtable holds function addresses of virtual functions only.

We can see that rdx holds the address of our vtable, which is 0x555555557d88, and the address of our first virtual function is 0x0000555555555190.

Lets see where the typeinfo for Ex1 takes us to:

Here we have a __class_type_info object having vptr to __class_type_info vtable, and then the typeinfo name which is Ex1.

Now ends our constructor Ex1…

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov [rax], rdx

nop

pop rbp

retn

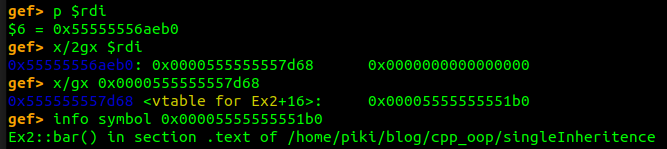

Lets take a view at GDB too…

So once we return from our Ex1 constructor, this is what things are actually going to look like!

When we return back to Ex2 constructor, we see that the Ex2’s vtable actually overwrites the vptr currently holding Ex1 vtable’s address in our object. See this disassembly:

lea rdx, off_3D68

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov [rax], rdx

nop

leave

retn

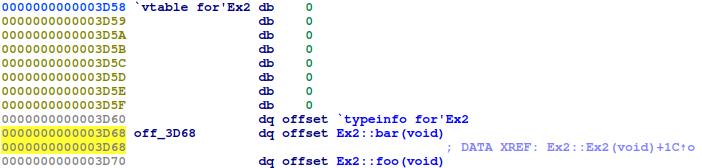

If we double click our off_3D68….

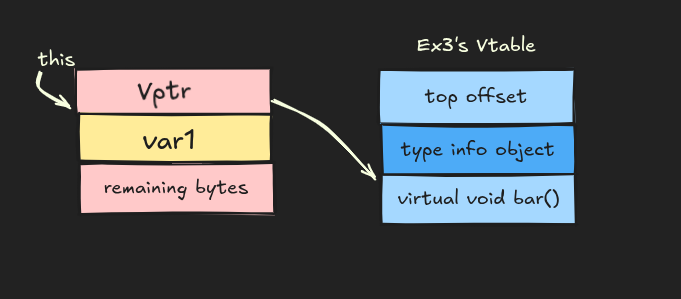

We see our vtable for Ex2’s vtable… this makes our object look like….

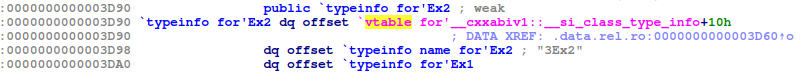

…in memory…. Lets now see what our typeinfo object looks like.

This is it in IDA. One very important thing we notice here, is that the vptr points to __si_class_type_info’s vtable. Let’s…

Meet __si_class_type_info!

We didn’t see this one before. __si_class_type_info too is the GCC C++ ABI implementation for classes with Single Inheritance (this is where si comes from). It’s part of the RTTI that handles classes containing only a single, public, non-virtual base at offset 0x0. Lets take a look at how it lives in the C++ Standard library…

public:

const __class_type_info* __base_type;

explicit __si_class_type_info(const char *__n, const __class_type_info *__base) : __class_type_info(__n), __base_type(__base) { }

We see it inherits from __class_type_info which we remember, got inherited from __type_info, so it does have the *__name. Apart from it, we can see it has a const __class_type_info* __base_type. It is a is a pointer to the base class’s typeinfo structure.

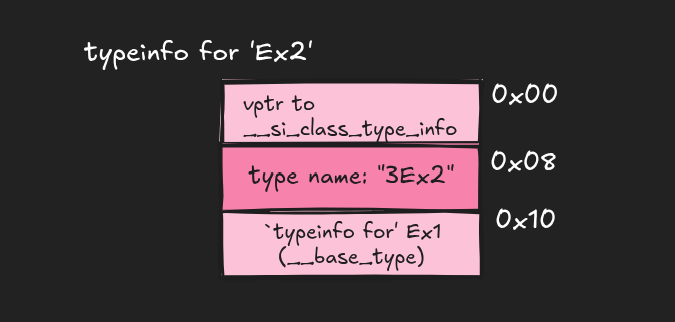

In the typeinfo object we saw in IDA:

- At

0x3D90, we have our vptr to__si_class_type_infovtable. - Then at

0x3D98, we have ourtypeinfo name for Ex2which is3Ex2. - And then at

0x3DA0, comes our typeinfo forEx1, which as defined in__si_class_type_info, is our__base_type.

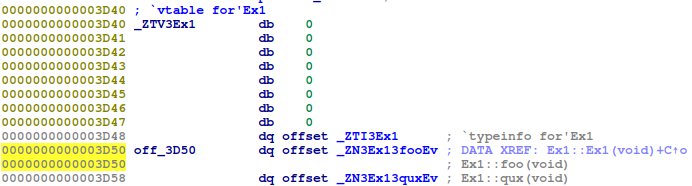

Once Virtual, Always Virtual

But why does Ex2’s vtable hold addresses for 2 virtual functions, when we only declared foo() as virtual and bar() was non-virtual? That’s because Ex2::bar() is an inherited virtual function. Even though we didn’t write virtual in Ex2, but because Ex1::bar() was virtual, so Ex2::bar() must be virtual too. It overrides Ex1::bar() in the vtable. Note that we declared foo() as virtual in Ex2. This is a new virtual function and doesn’t override anything and simply gets added to the vtable. So we see, that virtual-ness is inherited automatically. This way, you can believe Ex2’s bar() to be virtual too. So now our object looks something like this…

What if… we had another virtual function in Ex1, which isn’t even declared in Ex2? Well, that would still be in Ex2’s virtual table, because Ex1 is the primary base of Ex2, and then our virtual table will hold another entry for that function in the vtable. A primary base is such that it:

- Starts at offset 0 inside the derived object, and

- Shares its vptr (virtual pointer) with the derived object.

What if I make a call to foo() via my object obj? Which foo() will be called in this case… Lets see!

mov rdi, rax ; this

call Ex1::foo(void)

Naturally, we might assume that this call should’ve been made to Ex2::foo() since our object is of Ex2 type, but recall static binding. At compile time the compiler sees Ex1* obj calling foo(). Ex1::foo() is non virtual, so the compiler resolves the call based on the pointer type (Ex1*), and not the actual object type and hence generates call Ex1::foo(void). This we talked about call to foo(), but what happens….

When the compiler refuses to decide?

……what if we want to call bar()? Come see…

obj->bar();

Lets dive in to what will happen in such a scenario.

mov rax, [rbp+var_18] ;this

mov rax, [rax]

mov rdx, [rax]

mov rax, [rbp+var_18]

mov rdi, rax

call rdx

Let me explain the assembly now… rax holds our this pointer.

At line 19, we dereference the address stored in rax, and overwrite rax with whatever thing we got after dereferencing, which will be the address of Ex2’s vtable.

Great! Now we further pick the contents from the address of our vtable, and move them in rdx, which will be the address of our virtual function bar().

We load our this pointer in rdi, and then call rdx. Since rdx has the address of my first virtual function in Ex2’s vtable, so that will be called. Here we notice a different way of calling functions. This is an indirect call. Although Ex1 declared bar() as virtual, which automatically made Ex2::bar() virtual through inheritance, the runtime polymorphism mechanism accurately identified that the actual object was of type Ex2 and hence invoked Ex2’s overridden version of bar(). This is exactly what we call dynamic binding, where the function is chosen at runtime based on the actual object, not just the pointer type. This shows how virtual functions enable runtime polymorphism, which means that the function call is resolved based on the actual object type rather than the pointer type.

Multiple Parents with virtual functions…

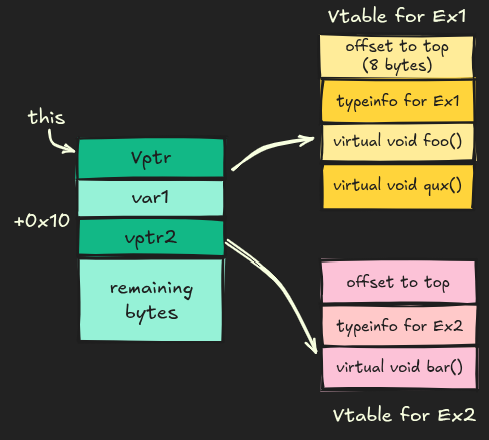

Now we’ll see take a quick look at how things get involving virtual functions when we have a case of multiple inheritance. Below is the example which I’ll be using to demonstrate this:

class Ex1

{

private:

int var1;

public:

virtual void foo()

virtual void qux()

};

class Ex2

{

public:

virtual void bar()

};

class Ex3: public Ex1, public Ex2

{

private:

int var2;

public:

virtual void baz()

virtual void foo()

};

We create an object in main like…

Ex3 *obj = new Ex3;

We’ll jump straight where our Ex3 constructor is called with our this pointer storing the address of our object that is 0x55555556aeb0 stored in rdi.

mov rdi, rbx ; this

call Ex3::Ex3(void)

And then in our Ex3 constructor….

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 10h

mov [rbp+var_8], rdi

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov rdi, rax ; this

call Ex1::Ex1(void)

Note, that we first call Ex1 constructor, because it comes first in the order of inheritance, and is our primary base.

mov [rbp+var_8], rdi

lea rdx, off_3D50 ;vtable for Ex1

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov [rax], rdx

Here we load the effective address of our Ex1’s vtable in rdx.

We see two entries in the vtable, of the two virtual member functions Ex1 class has. We don’t need much explanation of the vtable, because we’re already very much familiar with that. Lets also take a look at the typeinfo object because… why not?

lets take a look at how the object looks like in real…

and…

We’re done with our call to primary case, so lets return back to our

We’re done with our call to primary case, so lets return back to our Ex3’s constructor.

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

add rax, 10h

mov rdi, rax ; this

call Ex2::Ex2(void)

Once we move our object’s address to rax, we see, that it gets incremented by 0x10… This is because recall, our Ex1 class consists of a data member var1 of 4 bytes since it’s an integer. Add those 4 bytes, plus the vptr we just installed in our object. Because of alignment restrictions, we add 16 bytes (0x10) rather than 12. After 16 bytes addition, our address is 0x55555556aec0. So we’re actually jumping over those bytes. Lets call our Ex2 constructor now.

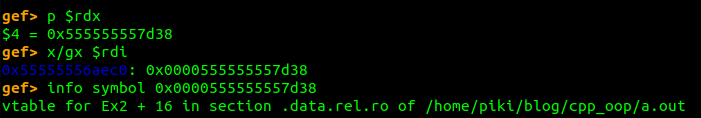

mov [rbp+var_8], rdi

lea rdx, off_3D38

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov [rax], rdx

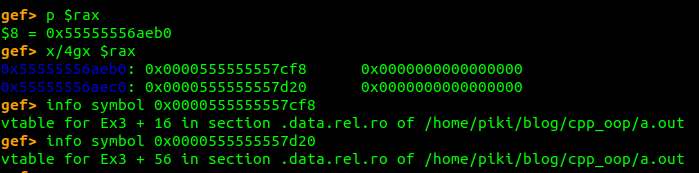

Lets see what our Ex2 vtable’s address is which gets written at 0x55555556aec0.

Our object now looks like this…

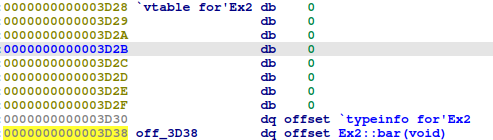

and now, lets take a peek into what Ex2’s vtable looks like…

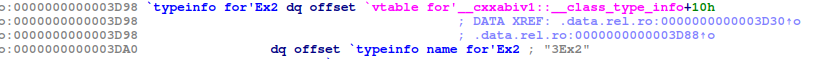

Also, lets take a look at its typeinfo:

Ex2’s vtable consists of only one virtual function entry, that is bar(). So nothing new here. Lets return and the assembly we encounter right after returning is…

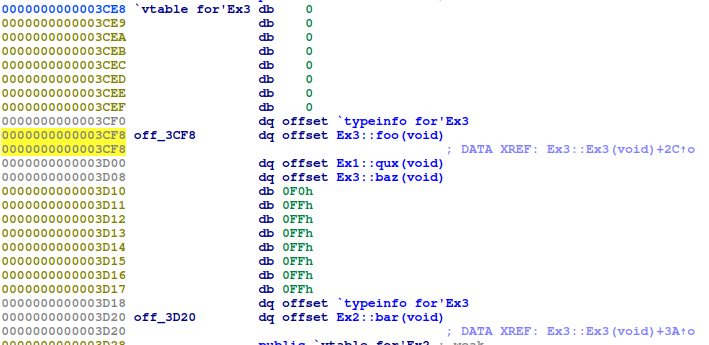

lea rdx, off_3CF8

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov [rax], rdx

We’re overwriting Ex1’s vtable entry with the vtable of Ex3. But what does Ex3’s vtable look like?

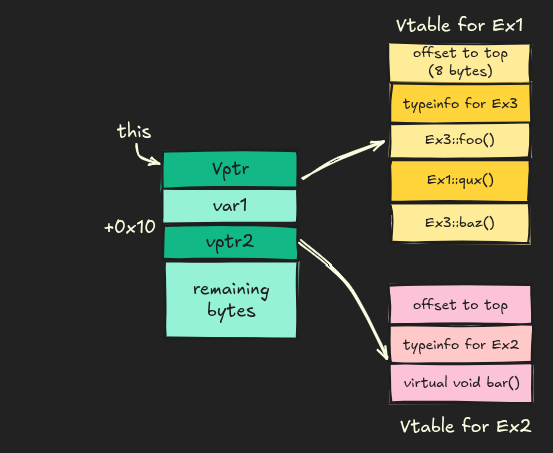

Oh wow… this is a pretty big vtable. Lets just focus on the first half for now till 0x3CF8 which we’ll call our primary vtable… We see entries for three virtual functions. They are Ex3::foo(), Ex3::baz() and Ex1::qux().

Vtable nitty gritty..

The vtable starts at 0x3CE8 with eight consecutive zero bytes which is the offset-to-top. This zero indicates that this vtable belongs to the primary base class. In other words, when we use this vtable for an Ex3 object, the this pointer already points to the very beginning of the complete object (offset 0x0), so no pointer adjustment is required. After the offset to top, we have our typeinfo for Ex3.

The primary vtable then stores the virtual function pointers, starting with Ex3::foo(), then Ex1::qux(), and finally Ex3::baz(). This arrangement shows that Ex3::foo() overrides the virtual function Ex1::foo() from its primary base class, because we can see Ex1::qux() but we can’t see Ex1::foo() and can see Ex3:foo() instead.

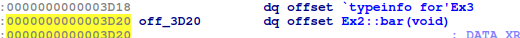

Lets continue to our secondary vtable as we’ll call it, which is at 0x3D10, which begins with another offset to top value. But this time it’s not all zeroes as we’ve seen in the previous cases, but is actually a negative integer, -16 in two’s complement. This indicates that to reach the start of the complete Ex3 object from this secondary base class part, we need to move back 16 bytes in memory. This secondary vtable also has the same typeinfo object for Ex3, and then comes Ex2::bar(). The Ex2 in Ex2::bar() suggests that it is not overridden by Ex3, and that Ex2 is the secondary base class.

Lets see this in GDB:

We have overwritten our vptr with the address of Ex3’s vtable, while at offset of +16 our Ex2’s vtable still remains intact.

Lets move forward with the disassembly:

lea rdx, off_3D20

mov rax, [rbp+var_8]

mov [rax+10h], rdx

Now we have gone ahead +16 bytes (0x10) from our this pointer, and overwritten that memory location with another address… double clicking on off_3D20 reveals, that it is actually our Ex3 vtable (Secondary vtable).

Lets see our object now:

The nuts and bolts of __vmi_class_type_info..

We are almost done, but lets first see how the typeinfo looks like for Ex3?

Unlike before, where we had __class_type_info and __si_class_type_info, here we have __vmi_class_type_info, and this is huge! __vmi_class_type_info is also the GCC C++ ABI implementation for classes with Virtual or Multiple Inheritance or both (this is where vmi comes from). Lets first look at __vmi_class_type_info’s constructor and some data members:

public:

unsigned int __flags; // Details about the class hierarchy.

unsigned int __base_count; // Number of direct bases.

// The array of bases uses the trailing array struct hack so this

// class is not constructable with a normal constructor. It is

// internally generated by the compiler.

__base_class_type_info __base_info[1]; // Array of bases.

explicit __vmi_class_type_info(const char* __n, int ___flags): __class_type_info(__n), __flags(___flags), __base_count(0) { }

It calls the parent class constructor with the name as an argument ` __class_type_info(__n),stores the flags parameter in the __flags member variable and initializes __base_count to 0. Recall that __type_info had a const char *__name;, which was inherited by __class_type_info. So we're simply passing it that. This is how our __vmi_class_type_info` typeinfo structure looks like:

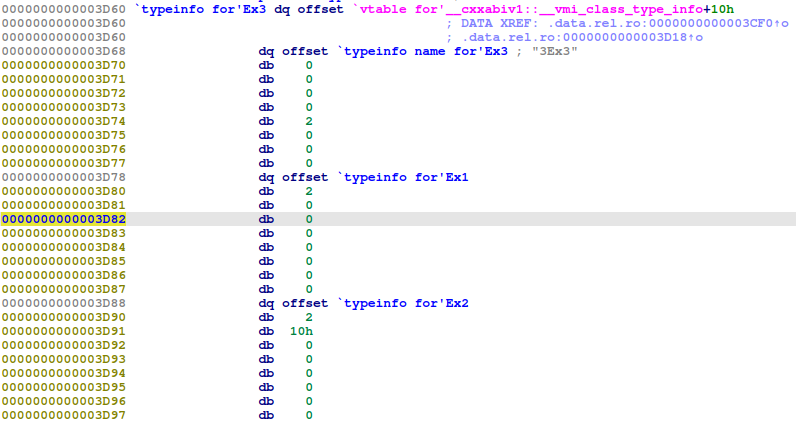

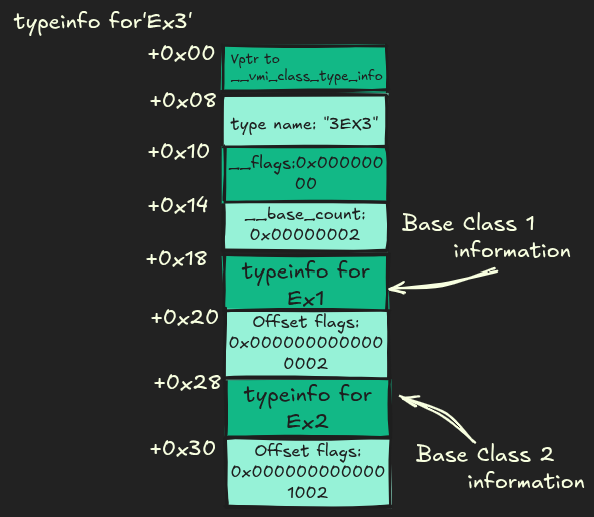

If we take a look at the typeinfo for Ex3 in IDA again, so we get to know, that at:

- At offset

0x3D60we have a pointer to__vmi_class_type_infovtable. - At offset

0x3D68comes the mangled type name which here is"3Ex3". - At offset

0x3D70come our__flagswhich define what type of inheritance we’ve done and our class structure… They’re defined in our__vmi_class_type_infoclass as:enum __flags_masks { __non_diamond_repeat_mask = 0x1, // Distinct instance of repeated base. __diamond_shaped_mask = 0x2, // Diamond shaped multiple inheritance. __flags_unknown_mask = 0x10 };We just saw

__flagsas an argument to our__vmi_class_type_infoconstructor. The enum__flag_masksis like a map that explains what each bit position means, while__flags(4 bytes) is the actual data that holds the bit pattern for this class. Since we haven’t done any complex inheritance, so this 32 bit field is all zeroes. - Then at offset

0x3D74comes the number of direct, proper base classes we have, which is our__base_count, and since we have 2 base classes, so it’s set as 2. - At offset

0x3D78we have our__base_info[0]which is of type__base_class_type_info. Each base class will get an index inside__base_infoarray. From standard C++ library…

// Helper class for __vmi_class_type.

class __base_class_type_info

{

public:

const __class_type_info* __base_type; // Base class type.

#ifdef _GLIBCXX_LLP64

long long __offset_flags; // Offset and info.

#else

long __offset_flags; // Offset and info.

#endif

enum __offset_flags_masks

{

__virtual_mask = 0x1,

__public_mask = 0x2,

__hwm_bit = 2,

__offset_shift = 8 // Bits to shift offset.

};

};

First we’re going to have a pointer to our base class. Since Ex1 is inherited first, so we’ll see a pointer to typeinfo for Ex1 at 0x3D78.

- Then comes a ‘2’ at offset

0x3D80, which is__base_class_type_info::__offset_flags(8 bytes), representing that we have inheritedEx1publicly (as we can see__public_maskis0x2). - Then we have our offset to top at which is a part of our

__offset_flags,0x3D81, which here is 0 bytes asEx1is the primary base class at start of object. - At

0x3D88, we have our__base_info[1]with__base_typepointer pointing totypeinfo for Ex2. - At offset

0x3D90we have our__base_class_type_info::__offset_flagswhich represents that we inheritedEx2publicly and then later at0x3D91we have an offset of0x10as seen in the figure.

Lets return back to our main now…. Where we finish execution of our program with the function epilogue.

Pure virtual functions and crash landings…

Till now, we’ve only seen how simple virtual functions work. Now let’s take a look at what pure virtual functions are. Well, pure virtual functions let us define a kind of ‘blueprint’ for a class, something that says every derived class must provide its own version of this function which is pure virtual. Let’s see an example:

class Animal {

public:

virtual void speak() = 0; // pure virtual

};

class Dog : public Animal {

public:

void speak() override { write(1,"Woof\n", 5); }

};

we define pure virtual functions by equating them to 0 as seen in the above example. Here, Animal is just an idea, a concept, it doesn’t make sense to create a generic Animal directly because every animal speaks differently. By making speak() pure virtual (= 0), we’re forcing our derived class Dog to provide its own version of speak. Pure virtual functions let us create an interface, which is a class that only defines what functions should exist and not how they work Such classes can’t be instantiated, only classes derived from them can. If I try to instantiate Animal class by doing:

Animal a;

I got the following compile time errors:

pure.c: In function ‘int main()’:

pure.c:15:12: error: cannot declare variable ‘a’ to be of abstract type ‘Animal’

15 | Animal a;

| ^

pure.c:4:7: note: because the following virtual functions are pure within ‘Animal’:

4 | class Animal {

| ^~~~~~

pure.c:6:18: note: ‘virtual void Animal::speak()’

6 | virtual void speak() = 0; // pure virtual

| ^~~~~

Our compiler forbids us from creating an Animal object. However, if i create an Animal pointer pointing to Dog object, that’s totally fine.

Animal* a = new Dog(); //outputs Woof

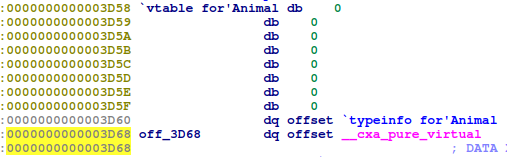

We know how objects get instantiated, and how the vtable of the primary base gets stored right at our object’s starting address in case of single inheritance involving virtual functions, so we won’t dive into that, but we’d like to see the Animal vtable, since it has a pure virtual function.

We see a strange kind of entry where our vptr points to, which is __cxa_pure_virtual. Later the Animal vtable gets overwritten by Dog’s vtable, as we’ve already seen in inheritance cases, so we never make a call to __cxa_pure_virtual, but lets try triggering a call to it, to see what happens.

Triggering __cxa_pure_virtual…

This is the piece of code we’ll be using to force our program to make a call to __cxa_pure_virtual.

class Animal {

public:

Animal();

virtual void speak() = 0;

};

void trigger(Animal* a)

{

a->speak();

}

Animal::Animal() { //constructor body

trigger(this); // calls 'f' while B is being constructed

}

class Dog : public Animal {

virtual void speak() { }

};

The code is quite self explanatory. When our Dog object gets instantiated, it invokes Animal constructor, which calls the method trigger() with the this pointer as an argument, and trigger() tries calling Animal::speak(). Since we are allowed by the compiler to instantiate our Dog class, so we do

Dog d;

On compiling, it does get compiled successfully, but on running it, we face some errors which are:

pure virtual method called

terminate called without an active exception

Aborted (core dumped)

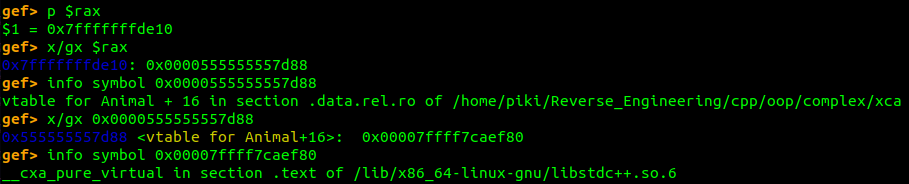

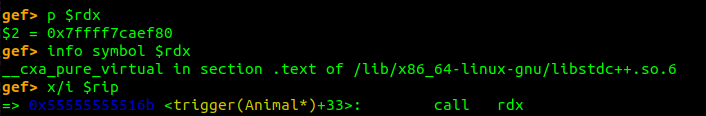

We did successfully make a call to a pure virtual function… but our program got aborted. We know what our Animal’s vtable looked like, it had a single entry for __cxa_pure_virtual() and this is exactly what was called then. If we take a look in GDB:

The address of our object is

The address of our object is 0x7fffffffde10 and its vtable is at 0x0000555555557d88. If we further look inside the vtable, we get the first entry to __cxa_pure_virtual.

We move the address of our first vtable entry inside

We move the address of our first vtable entry inside rdx, and give it a call after which we reach inside the __cxa_pure_virtual() method.

0x00007ffff7caef84 <+4>: push rax

0x00007ffff7caef85 <+5>: pop rax

0x00007ffff7caef86 <+6>: mov edx,0x1b

0x00007ffff7caef8b <+11>: lea rsi,[rip+0xfc772] # 0x7ffff7dab704

0x00007ffff7caef92 <+18>: mov edi,0x2

0x00007ffff7caef97 <+23>: sub rsp,0x8

0x00007ffff7caef9b <+27>: call 0x7ffff7ca1ed0 <write@plt>

0x00007ffff7caefa0 <+32>: call 0x7ffff7c9e2e0 <std::terminate()@plt>

This is the disassembly of our __cxa_pure_virtual() method. We see it writes some string at address 0x7ffff7dab704 to stdout, and calls terminate().

This is the same string we saw in our output when we triggered a call to Animal::speak(). If we see this in our C++ Standard library…

extern "C" void

__cxxabiv1::__cxa_pure_virtual (void)

{

writestr ("pure virtual method called\n");

std::terminate ();

}

So now we know why calls to pure virtual functions terminate, because they internally call std::terminate().

The end….

And I guess… this is it for now.

Happy reversing!